Packaging a Python project with setuptools

I do not like when things are not properly organized. I like to have a clear

structure in my projects, and I like to have a clear way to package them.

Lately, Python decided to reunify its packaging tooling around pyproject.toml.

Unfortunately, only few documentations are available on how to use it properly

and how to mix it with other features such as testing or documentation. In this

article, I will present a simple scaffolding for a Python project that uses

setuptools as a builder, pytest for testing and sphinx for documentation.

Project Hierarchy

Our project will only contain one module and one function for the sake of simplicity. The hierarchy of the project will be as follows:

myproject.git/

├── myproject/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── hello.py

├── tests/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── test_hello.py

├── LICENSE.md

├── README.md

└── pyproject.toml

The content of myproject/hello.py is the following:

"""A Hello module in the myproject project"""

def hello() -> None:

"""Hello function"""

print("Hello World!")

The content of tests/test_hello.py is the following:

"""A test case to check the myproject.hello module"""

import pytest

from myproject.hello import hello

def test_hello(capfd):

"""Test the hello function"""

hello()

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "Hello World!\n"

assert err == ""

Then, myproject/__init__.py will only contain the version of the project:

"""Main module for myproject"""

import myproject.hello

__version__ = "0.1.0"

The other tests/__init__.py is empty. The LICENSE.md contains a BSD-2-Clause

license, the README.md contains the project description and pyproject.toml

contains the following:

[build-system]

build-backend = "setuptools.build_meta"

requires = ["setuptools"]

[project]

name = "myproject"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "My scaffolding project example"

authors = [

{name = "John Doe", email = "john.doe@springfield.org"},

]

license = "BSD-2-Clause"

license-files = ["LICENSE.md"]

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.6"

dependencies = [

'importlib-metadata; python_version<"3.10"', # Metadata access

"pytest", # Testing framework

]

Note: The importlib-metadata dependency is required for Python versions

prior to 3.10. It is used by setuptools to access metadata in

pyproject.toml.

It is also important to note that the requirements.txt file is not used

anymore. The dependencies are declared in pyproject.toml and only there. The

syntax used to describe the dependencies here is also the one from PEP

508, so nothing new to learn.

Build the Project

As usual in Python development, we will use a virtual environment to isolate the project dependencies. First, we create and activate the virtual environment:

#> python3 -m venv .venv

#> source .venv/bin/activate

Note: The virtual environment is created in the .venv directory at the

root of the project. You can choose another name if you want, but this one is

quite standard. And, finally, you can use deactivate to quit.

Then, we get all the project dependencies inside our virtual environment and install the project in editable mode:

#> pip install -e ./

Installing build dependencies ... done

Getting requirements to build wheel ... done

Preparing metadata (pyproject.toml) ... done

...8<...

Successfully built myproject

Installing collected packages: myproject

Attempting uninstall: myproject

Found existing installation: myproject 0.1.0

Uninstalling myproject-0.1.0:

Successfully uninstalled myproject-0.1.0

Successfully installed myproject-0.1.0

Note: The -e option is for editable mode. It means that the project is

installed in development mode, and any change in the source code is immediately

available without reinstalling the project each time you change the code. You

may omit this option if you are installing the project in a production environment.

Then, we can run the tests:

#> pytest

============================= test session starts ==============================

platform linux -- Python 3.12.4, pytest-8.3.2, pluggy-1.5.0

rootdir: .../myproject.git

configfile: pyproject.toml

collected 1 item

tests/test_hello.py . [100%]

============================== 1 passed in 0.07s ===============================

We are half-way through our goals now. We have a project with a module, a test suite, and a way to build and test it. The next step is to add code coverage and documentation generation. But before that, lets be perfectionist and try to get rid of some annoying technicalities.

One version to rule them all

You may have noticed that the version of the project is defined in

pyproject.toml but also in myproject/__init__.py. It is a common practice to

have only one place where the version of the project is defined because it

prevents inconsistencies. For that, we will use the pyproject.toml dynamic

variables as follows:

...

[project]

dynamic = ["version"] # Variables handled in dynamic metadata

...

[tool.setuptools.dynamic]

version = {attr = "myproject.__version__"} # Get version from package dynamically

...

And we remove the old version = "0.1.0" line from pyproject.toml. Now, the

version of the project is only defined in myproject/__init__.py.

Much cleaner, isn’t it? Lets go for code coverage now.

Add Code Coverage

This one will be quite easy. We use the pytest-cov plugin and we only modify

pyproject.toml to add the plugin and give it a few options:

...

dependencies = [

"pytest", # Testing framework

"pytest-cov", # Code coverage plugin

]

[tool.pytest.ini_options]

addopts = [ # Add options for pytest

"--cov=myproject",

"--cov-report=html",

"--cov-report=term",

"--cov-branch",

]

Then, do not forget to install the new dependencies:

#> pip install -e ./

And, we can run the tests with code coverage:

#> pytest

============================= test session starts ==============================

platform linux -- Python 3.12.4, pytest-8.3.2, pluggy-1.5.0

rootdir: .../myproject.git

configfile: pyproject.toml

plugins: cov-5.0.0

collected 1 item

tests/test_hello.py . [100%]

---------- coverage: platform linux, python 3.12.4-final-0 -----------

Name Stmts Miss Branch BrPart Cover

---------------------------------------------------------

myproject/__init__.py 2 0 0 0 100%

myproject/hello.py 2 0 0 0 100%

---------------------------------------------------------

TOTAL 4 0 0 0 100%

Coverage HTML written to dir htmlcov

============================== 1 passed in 0.07s ===============================

Note: The code coverage HTML report is available in the htmlcov directory.

You can open the index.html in your browser to see the coverage report.

The option --cov-branch is used to check the coverage of the branches in the

code. It give a much more accurate view of the code coverage than the simple

line coverage and can capture some corner cases that could escape to too simple tests.

So, lets go for the last step, automate this damn documentation generation which is always a pain to write and maintain if it is outside of the code.

Automated Documentation Generation

Documentation generation can be achieved with several tools, but the most common

one seems to be Sphinx. So, we will use it here with its ‘ReadTheDocs’ theme.

First, lets declare the dependency in pyproject.toml:

dependencies = [

"sphinx", # Documentation generator

"sphinx_rtd_theme", # ReadTheDocs theme for Sphinx

]

Then, do not forget to install the new dependencies, ‘again’:

#> pip install -e ./

Unfortunately, Sphinx does not provide yet a way to fit all its configuration in

pyproject.toml. There are some ongoing projects to make this possible, but

they seems to be in early stage and I wanted something that works now. So, we

will use the standard method to setup Sphinx (note that it may change in the

future). First, we will use the scaffolding provided by Sphinx:

#> sphinx-quickstart docs

Welcome to the Sphinx 7.4.7 quickstart utility.

Please enter values for the following settings (just press Enter to

accept a default value, if one is given in brackets).

Selected root path: docs

You have two options for placing the build directory for Sphinx output.

Either, you use a directory "_build" within the root path, or you separate

"source" and "build" directories within the root path.

> Separate source and build directories (y/n) [n]: n

The project name will occur in several places in the built documentation.

> Project name: myproject

> Author name(s): John Doe

> Project release []: 0.1.0

If the documents are to be written in a language other than English,

you can select a language here by its language code. Sphinx will then

translate text that it generates into that language.

For a list of supported codes, see

https://www.sphinx-doc.org/en/master/usage/configuration.html#confval-language.

> Project language [en]: en

Creating file docs/conf.py.

Creating file docs/index.rst.

Creating file docs/Makefile.

Creating file docs/make.bat.

Finished: An initial directory structure has been created.

You should now populate your master file docs/index.rst and create other documentation

source files. Use the Makefile to build the docs, like so:

make builder

where "builder" is one of the supported builders, e.g. html, latex or linkcheck.

Right now, the generated documentation will not be really interesting. It will

requires some more work to be useful. First, we will modify docs/conf.py to

customize a few things. Add the following lines:

import myproject

...

release = myproject.__version__

...

extensions = ["sphinx.ext.autodoc"]

...

html_theme = "sphinx_rtd_theme"

...

So, the first and the second line fix the version of the project and prevent

inconsistencies (yes, again…). The third line adds the autodoc extension to

the Sphinx configuration to grab documentation directly from the docstrings in

the code. Finally, the last line sets the theme of the documentation to the

‘ReadTheDocs’ theme.

Before keep going, we need to generate a couple of rst files from the docstrings

in our code. We will use the sphinx-apidoc tool for that and we execute it

from the root of the project:

#> sphinx-apidoc -o docs/ myproject

The -o docs option tells Sphinx to put the generated files in the docs

directory. The myproject argument is the name of the package to document. It

will generate modules.rst and myproject.rst in docs/ that we will have to

include in docs/index.rst as follow:

myproject documentation

=======================

This is our wonderful project documentation.

.. toctree::

:maxdepth: 2

:caption: Contents:

modules

Indices and tables

==================

* :ref:`genindex`

* :ref:`modindex`

* :ref:`search`

The .. toctree:: directive tells Sphinx to include the modules.rst file in

the documentation. The :maxdepth: 2 option tells Sphinx to include only the

first two levels of the documentation. The :caption: Contents: option sets the

title of the included section.

Now, we can finally build the documentation:

#> cd docs

#> make html

Running Sphinx v7.4.7

loading translations [en]... done

loading pickled environment... done

building [mo]: targets for 0 po files that are out of date

writing output...

building [html]: targets for 0 source files that are out of date

updating environment: 0 added, 0 changed, 0 removed

reading sources...

looking for now-outdated files... none found

no targets are out of date.

build succeeded.

The HTML pages are in _build/html.

#> firefox _build/html/index.html

Of course, the autogenerated Makefile can be modified to include the call to

sphinx-apidoc automatically. But, this is left as an exercise to the reader.

And, voilà! We have a project with a module, a test suite, code coverage, and documentation generation. All of this is automated and can be run with a few commands and is up-to-date with the last standard of Python packaging (see: this blog post). I hope you found this useful.

Create a Starter Script

Finally, we can add a main script as an entry point to the myprogram project.

We need to add a __main__.py file in the myproject package:

import argparse

from myproject import __version__

from myproject.hello import hello

def main():

"""

Starting point of the program.

"""

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument(

"-V",

"--version",

help="display the version of the program",

action="store_true",

)

args = parser.parse_args()

if args.version:

print(f"MyProgram: version {__version__}")

# Call our awesome hello function

hello()

return 0

Finally, we add a [project.scripts] section in the pyproject.toml to add the

name of our main script and its entry point in our code:

[project.scripts]

myproject = "myproject.__main__:main"

That’s it! Now, you can run your program with:

#> myproject

Hello World!

#> myproject --version

MyProgram: version 0.1.0

Code analysis with pylint

To finish, we can add a code analysis tool to our project. We will use pylint

here. It is a very powerful tool that can help you to improve the quality of

your code. It checks for coding standards, errors, and many other issues.

First, we need to add a .pylintrc file at the root of the project to:

[MAIN]

recursive = yes

[MESSAGES CONTROL]

disable =

Then, we can run the analysis on our project:

#> pylint --enable-all-extensions myproject

************* Module myproject.__main__

myproject/__main__.py:1:0: C0199: First line empty in module docstring (docstring-first-line-empty)

myproject/__main__.py:11:0: C0199: First line empty in function docstring (docstring-first-line-empty)

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Your code has been rated at 8.67/10

We can then decide to fix the problem or ignore all the C0199

(docstring-first-line-empty) warnings by adding it to the disable option in

the .pylintrc file.

[MAIN]

recursive = yes

[MESSAGES CONTROL]

disable = docstring-first-line-empty

#> pylint --enable-all-extensions myproject

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Your code has been rated at 10.00/10 (previous run: 8.67/10, +1.33)

Another way to ignore a warning on a specific occurrence is to add a comment in the code:

...

def main():

# pylint: disable=docstring-first-line-empty

"""

Starting point of the program.

"""

...

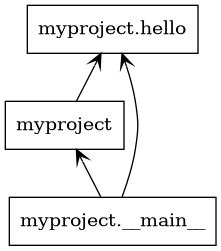

pylint package comes also with a pyreverse tool that can generate UML

diagrams of your project. It can be used to visualize the class hierarchy of

your project and the packages dependencies. As our example code has no classe,

we will focus on packages only (but classes are working the same way).

pyreverse generates a packages.dot file that can be converted to a PNG image

with the dot tool from the graphviz package:

#> pyreverse myproject

#> dot -Tpng packages.dot > packages.png